Why dietary guidelines are irrelevant for the obesity pandemic

The problem is much deeper, and the focus on the guidelines is a distraction

One of my original hopes in commenting about Covid was that, in publicly taking a strongly anti-establishment position, my audience might be able to relate a little better to what I was saying on other topics. It might, in other words, give me some credibility with the people who I was trying to reach when I wrote about misinformation in health and nutrition.

Despite having my life wrecked by that decision, I haven’t radically changed in my scientific orientation. I have become much more open-minded to the possibility that I might be wrong on any given topic, and I don’t simply dismiss as “crazy” positions that are radically foreign to mine. I’m genuinely sympathetic to the “absolute craziest ideas” these days, because some of what I formerly regarded as some of the “absolute craziest ideas”—such as the idea that lockdowns were counterproductive during the pandemic—I ended up actually believing as I became more informed.

Furthermore, as the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend showed through ample historical examples: sometimes hokey ideas, even hokey ideas contradicted by available evidence, end up being right. One such hokey idea that is very important that I hope to write about at some point in the future, is the idea that the Earth revolves on its axis, an idea that was overwhelmingly (apparently) contradicted by the evidence at the time it was proposed by Galileo. An evidence-based perspective would have rightly rejected Galileo’s proposal, as most of his contemporaries did. But the idea stayed alive and eventually the evidence both caught up with Galileo’s hypothesis, as did the interpretations of the existing data. Galileo, although he sometimes even used sleights of hand to compensate for the lack of evidence supporting his theories, was proven right—but there was no way to know that he was right until much later.

There are countless other examples besides the Galileo one. What Feyerabend called “counterinduction”—i.e., proposing hypotheses that directly contradict available evidence—is not an aberration of science but one of the most important ways that it has progressed historically. Without it, most of the major fields of physics would not exist, and some of the most important and life-saving medicines that we have today would have long ago been relegated to the dustbin of pharmaceutical history. Part of being a good scientist, then, means being open to the possibility of being radically and fundamentally wrong—even when the evidence seems to support your position.

Yet, while the medical establishment certainly gets a number of issues wrong—even as it dogmatically states that it is getting them right—I continue to believe that there is lots of misinformation on the anti-establishment side of things, too. I also believe that some of that misinformation on both sides, I might actually be wrong about being misinformation. In other words, I take a much more cautious and open-minded approach toward science communication than I used to.

So, I do not see myself as promoting any partisan agenda or promoting any one point of view, and I refuse to do such a thing. Rather, I see myself as communicating about what the science actually says so that people are better informed about how to make healthy decisions. Today, I merely presenting the facts as I see them.

So here’s my position: the obesity pandemic is caused by the overavailability of ultraprocessed, calorie-rich, hyperpalatable foods. This problem is exacerbated by the collapse of American food culture and structured eating arrangements, which mitigate the food availability problem in other countries. Lack of physical activity caused by “car culture” contributes further. Loneliness, social atomization, etc. further contributes. And possibly, hormonal disruption via industrial chemicals prevalent in our environment and all sorts of theories that strike me as rather strange and doubtful may in fact turn out to also be playing a major role in the obesity pandemic, as well.

Restricting food choices, such as with various popular diets, can induce weight loss, but that weight loss primarily takes place because food quality increases, satiety increases, and food choices decrease (reduced food choices means less drive to eat, a phenomenon that has been well-established by nutritional neuroscientists). These popular diets do not work through any particular “magic” of macronutrient manipulation but through simple caloric restriction, done indirectly and unintentionally through the macronutrient manipulation.

(We know this, in part, because one can still get fatter on a carbohydrate-restricted diet, or at minimum, plateau in weight loss. Simply restricting carbohydrates, in other words, is no guarantee that one will end up with ripped abs, looking like a Greek god. I know this, well, personally, as I know that in addition to being ketogenic or restricted in any other way, to get to that level of leanness, I need to count calories. People with more favorable genetics might be able to get away with more.)

That said, it may be the case that modest advantages accrue to folks who restrict macronutrients severely enough: I would never rule this out, since the studies do seem to support some modest effects in that direction. They might even be quite significant effects! But they haven’t been clearly shown in human experimental studies, that is, the data quality and the outcomes have not been clear enough to justify strong conclusions.

Anecdotes are certainly powerful, and the art of medicine consists in humbly and pragmatically relating what is known about science with what one is experiencing with this or that patient or group of patients. But anecdotes are often themselves very confounded and misleading.

Do my calf muscles feel sore because I am taking rosuvastatin? Or because I am running more than usual? Or is it a combination of both? Or maybe, I am just noticing more muscle soreness than I would because I know I am taking a statin? Or maybe the real reason my calf muscles are sore is that I am 225 pounds and running very long distances, whereas I have never been so large and doing so much cardiovascular training before and would have noticed it then too, if I had been, even without taking rosuvastatin? And so on.

Discerning the answer here definitively would take a lot of very careful self-experimentation. And my discussions with others indicate that almost nobody conducts such careful experiments. Rather, they may top taking the statin pragmatically, or switch to another statin, and observe what happens. They may be running significantly less when they make this switch. Or their muscles may have adapted. Then they conclude, fallaciously from a scientific point of view, that rosuvastatin indeed caused their muscle soreness. But there is no certainty in this conclusion because all of the relevant variables were not controlled for. Which is fine for individuals, because scientific certainty is not required to make practical decisions. But it is not fine for drawing firm scientific conclusions, because without the proper design to self-experimentation, such firm conclusions are not appropriate.

I’ve known some very intelligent people who swear up and down by this or that intervention for their own lives. But very rarely do such people have full control over the variables at play.

Doctors “knew”, for instance, for thousands of years that “bloodletting” acutely ill patients was very beneficial. And they “knew” this based on clinical experience. Yet when this belief was put to the test in one of the first ever clinical trials, it was shown that bloodletting acutely ill patients actually increased risk of dying by ten-fold. Correspondingly, we no longer bloodlet acutely ill patients.

Likewise, some people swear up and down that masking prevented their getting Covid. But the available randomized evidence simply does not bear out the contention that masking prevents the transmission of respiratory viruses transmitted via aerosols. Or if it does, the effect is quite modest, in the range of 10%, as Fauci has himself publicly stated.

I know that I have never contracted Covid (that I am aware of). Yet after 2020, I never masked. Should my conclusion be that masking actually causes Covid, since I know other people who have masked and gotten it, while I haven’t.

No, this would also be ridiculous. I cannot extrapolate from a few data points. Instead I follow the data.

So, given these caveats, and the expression of my position about the obesity pandemic, allow me to present some data about the food pyramid and the obesity rate in this and in other countries.

But before, I do, one final caveat. The dietary guidelines have certainly been influenced by industry. A quick perusal of the history around McGovern’s efforts to improve this country’s diet in the 1970s shows this very clearly. Thus, the dietary guidelines were watered down and distorted. The United States Department of Agriculture has two mandates: 1. protecting consumer health and 2. promoting American agriculture. These mandates can come into conflict with each other, and that is a serious problem, because the USDA plays the overwhelming role in determining what the dietary guidelines will look like.

Nor are the Dietary Guidelines distorted far away from what the science indicated, but rather, they are distorted to provide the interpretation of the science most favorable to industry. Thus, the current dietary guidelines are not unscientific—but that does not mean that they are not corrupted.

Yet things are still more complicated than that, for what does one mean by “corrupted”? One argument for some of the more watered-down versions of the guidelines is that these versions are more practical for the consumer—the consumer cannot be reasonably expected to follow some of the stricter (and likely more efficacious) recommendations that some more radical versions of the guidelines might make. Thus the guidelines compromise.

But is this a compromise between industry and consumer health? Or is it a compromise between what consumers are most likely going to want to do, and consumer health? Remember that industry does not directly impose itself upon the consumer, but rather, it creates what the consumer is most inclined to consume (this includes the creation of consumer demand through advertising—for, this creation of consumer demand could only occur if the consumer abides by it). And thus, when the Dietary Guidelines are “compromised” by industry, it might also just as reasonably be said that they are compromised by consumer choice—representing, as they do, a compromise between changes that we can reasonably expect the consumer to make, and what would be optimal in the best possible world.

Thus, I certainly do not eat according to the guidelines. I eat a diet more consistent with my own goals and preferences. I also think that the optimal diet is not the diet presented in the guidelines. Yet, nonetheless, I do not think the guidelines themselves were responsible for the obesity pandemic. The guidelines may be suboptimal; they may be influenced by industry or an excessive catering to typical consumer demand; and they may guide those looking for optimal health in the wrong direction. But they are not the cause of the pandemic, but rather, in some sense, a partial reflection of it.

The emphatic claims that the Dietary Guidelines caused the obesity pandemic are understandable: they identify an easy target, or scapegoat, and this allows people to vent their frustration. Unfortunately, however, the problem with scapegoats is that energy directed at scapegoats wastes precious energy without actually addressing the real problem. That, I maintain, is what the repeating uproar over the guidelines actually is: wasted energy directed at a convenient, but wrong, target.

The problem, as I have said, is that the obesity pandemic is being driven by much more fundamental and difficult to change forces. If only the Dietary Guidelines was the problem! Then we could just change the Guidelines, and with that, change our society. Unfortunately, things are much, much more difficult than that. It may very well be the case, as I believe, that the obesity pandemic is in part the result of having a free and prosperous society, in which case perhaps only a curtailment of freedom would be the kind of lever required to truly make a dent in the pandemic. Alternatively, as I hope (and dream—for a future post), the science of nutrition, in perfectly clarifying the actual nutritional causes and mechanisms of weight gain, might allow us more clarity in selecting and even designing foods in the future that may be much less prone to producing weight gain and obesity.

With that final caveat and explanation of my position, now I will make the above argument using one set of data. It certainly does not fully resolve the question. But, it provides a start: namely, I show that while guidelines are remarkably similar between countries (due to standardization across countries over time), the rate of obesity varies dramatically.

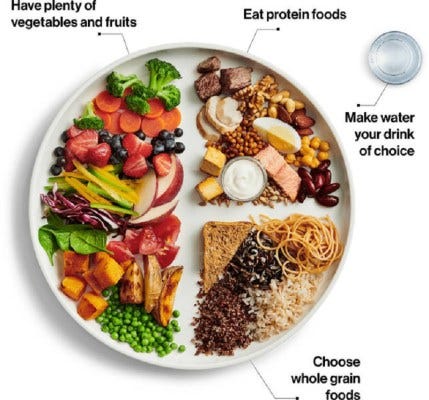

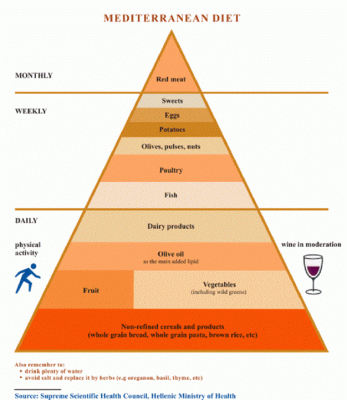

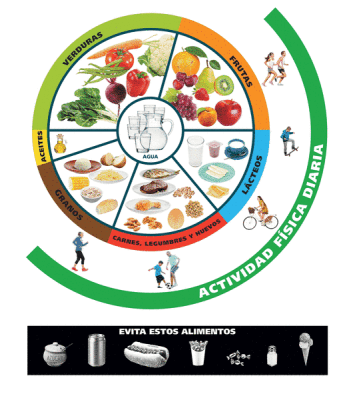

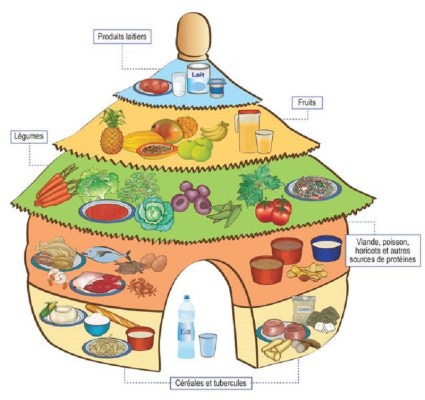

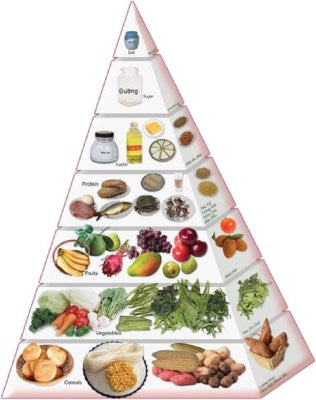

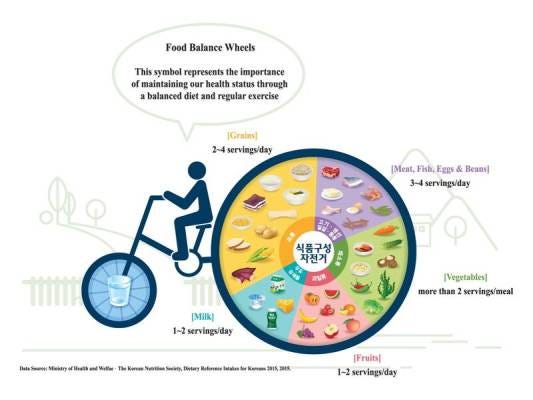

Take Japan, which has a famously low rate of obesity. Its “food pyramid” is very nearly an inverted American food pyramid:

Yes, there are marginal differences. A few fewer servings of grains, for instance. And a few more servings of vegetables. But the concept is the same. The Japanese diet is a grain-heavy diet.

Japan’s obesity rate? 3.6%.

America’s? 42%.

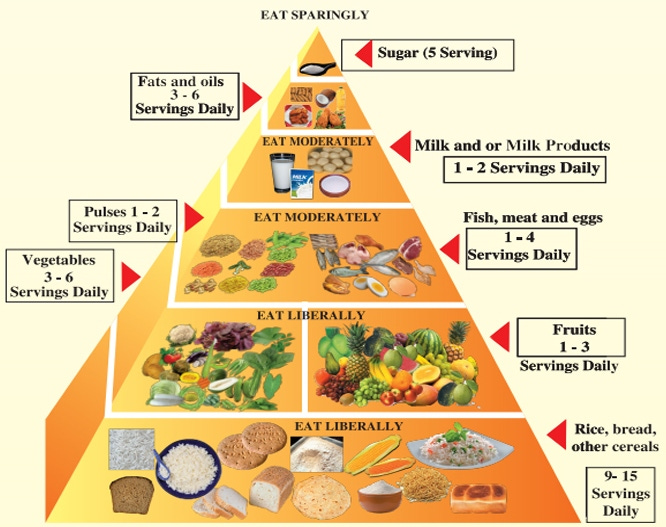

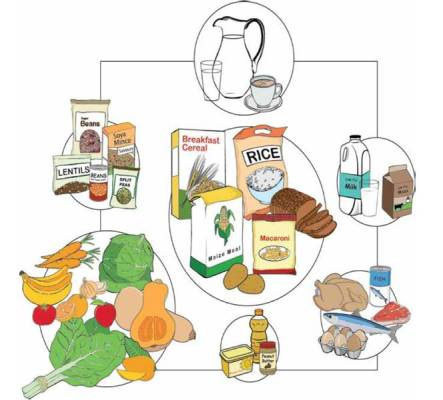

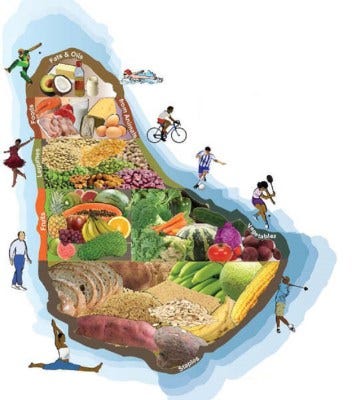

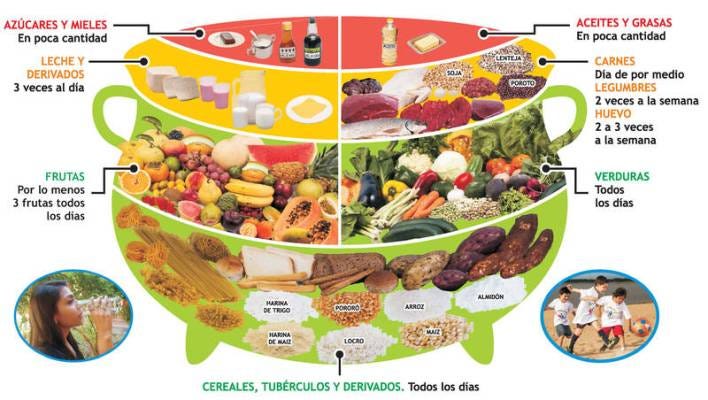

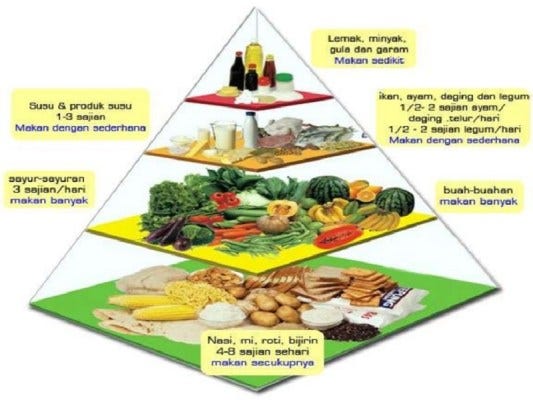

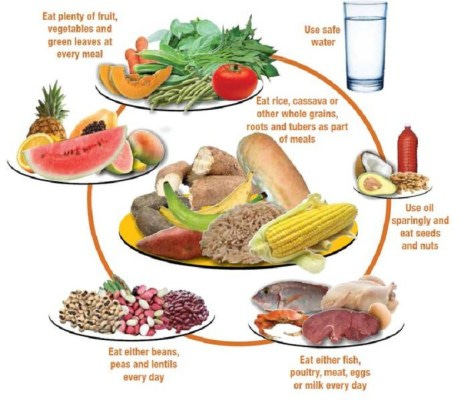

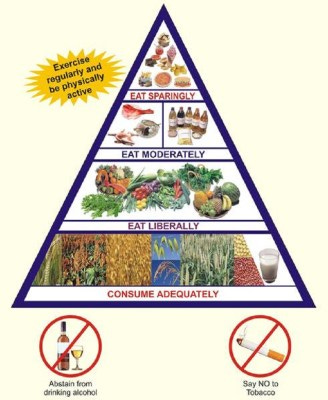

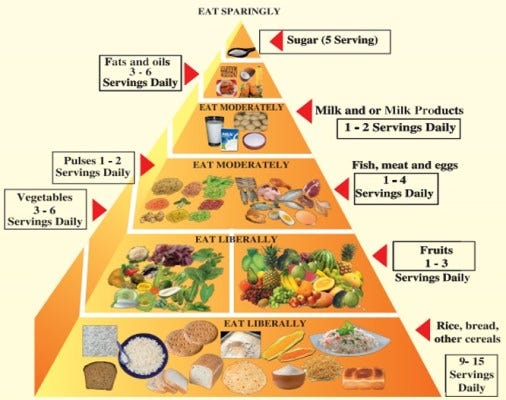

Or take Bangladesh, whose guidelines are even closer to America’s:

Bangladesh’s obesity rate? 3.6%.

America’s? 42%.

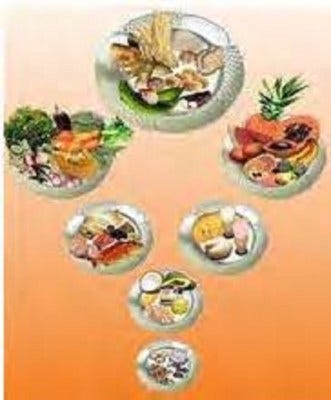

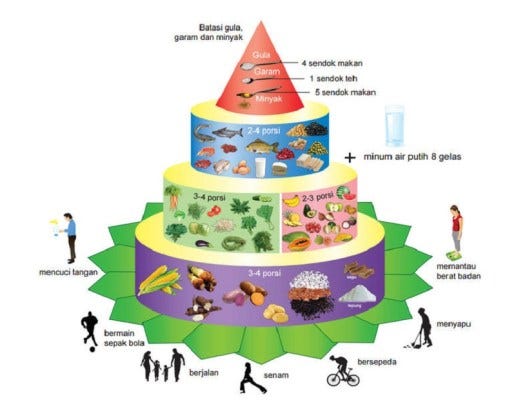

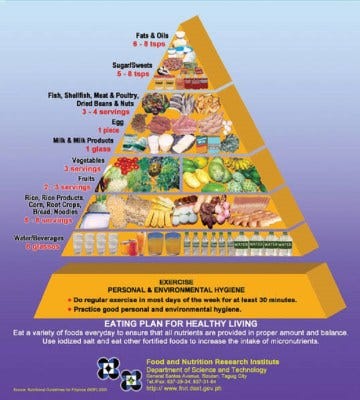

Or take Thailand, with an obesity rate of 10%. Its food pyramid looks much the same way:

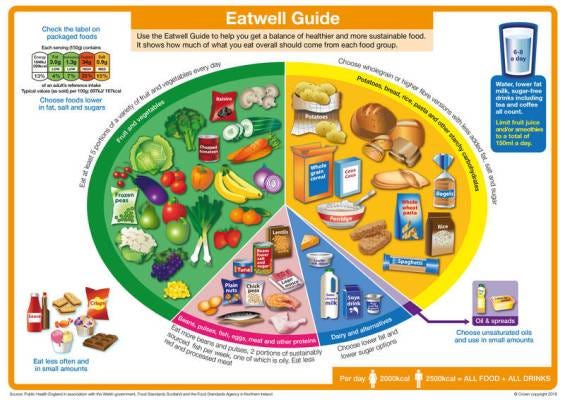

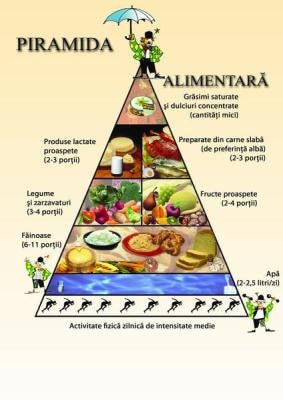

Now check out Ireland’s food pyramid:

Despite being decked out in vegetables and having very modest grain recommendations, much like Japan, it has an obesity rate that is a full ten times higher than Japan and close to that of the United States.

Thus, there seems to be very little relationship between the content of the Dietary Guidelines in each respective country and their obesity rate.

What this means is that while the Dietary Guidelines in each country may have some impact on the rate of obesity, that impact is so small that it is almost impossible to detect.

This shouldn’t be surprising. After all, who knows exactly what the dietary guidelines even say? Among those who do, have you ever heard a human being in your entire life say: “No, sorry, I can’t eat that right now. I’m following the dietary guidelines?”

It is quite a ridiculous proposition on the face of it.

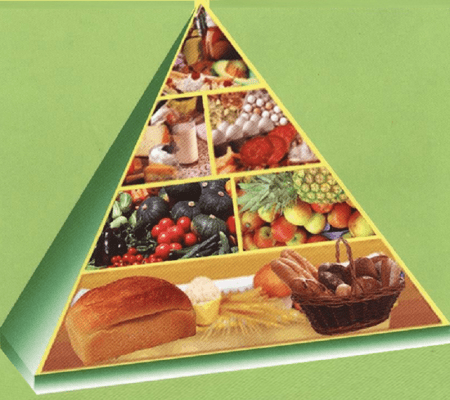

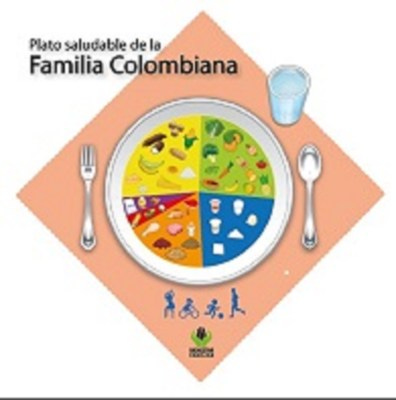

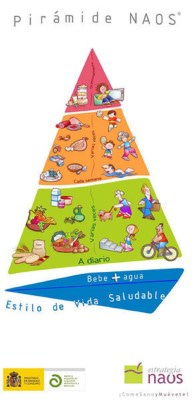

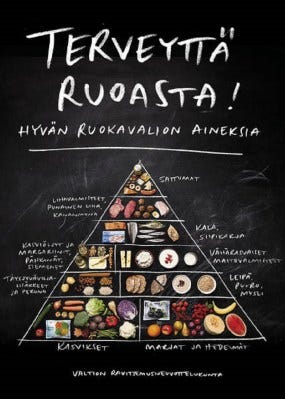

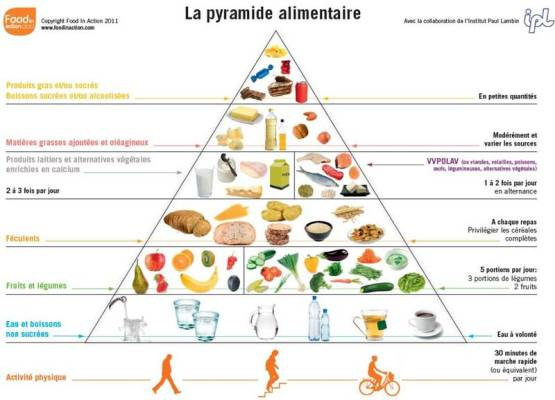

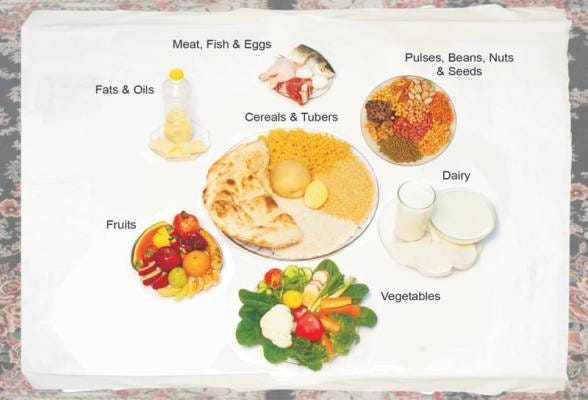

But to see that comprehensively, let’s look visually at these guidelines for each of these countries. You will see that these guidelines are all remarkably similar, that differences are quite small, and to the extent that differences may exist, they do not seem to strongly correlate to the rate of obesity.

I have included as many countries here as possible for your perusal—so that you know I am showing you the full truth. I am hiding nothing.

Scroll through, quickly or slowly, whichever you like. After you have scrolled to the bottom, we will address a criticism and quantify our conclusions further.

41.40% – Qatar

36.60% – Malta

34.40% – Antigua and Barbuda

34.20% – United Kingdom

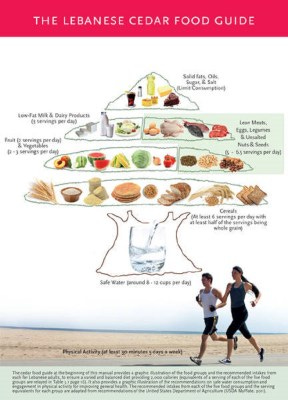

32% – Lebanon

31.90% – Saint Lucia

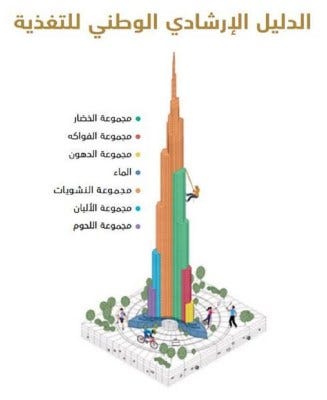

31.70% – United Arab Emirates

31.60% – Bahamas

31.40% – Ireland

30.20% – Fiji

30% – Turkey

29.40% – Canada

28.90% – Mexico

28.30% – Argentina

28.30% – South Africa

27.90% – Dominica

27.90% – Uruguay

27.80% – Dominican Republic

27% – Oman

26.50% – Latvia

26.20% – Bulgaria

26.20% – Croatia

25.70% – Costa Rica

25.60% – Venezuela

25.20% – Grenada

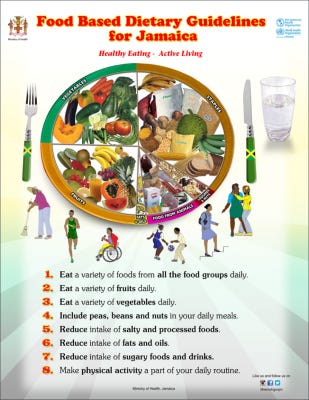

24.70% – Jamaica

24.60% – Cuba

24.60% – Poland

24.10% – Belize

23.70% – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

23.60% – Greece

23.10% – Australia

23.10% – Barbados

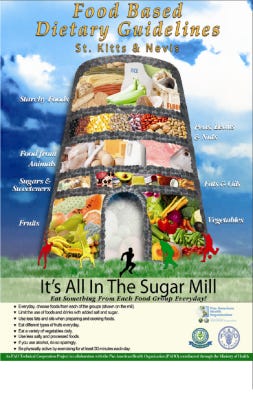

22.90% – Saint Kitts and Nevis

22.70% – Panama

21.70% – Albania

21.50% – Hungary

21.40% – Honduras

21.20% – Guatemala

21.20% – Iceland

20.90% – Estonia

20.30% – Paraguay

20.20% – Bolivia

20.20% – Colombia

20.20% – Guyana

20% – Spain

19.90% – Ecuador

19.90% – Finland

19.70% – Mongolia

19.70% – Peru

19.60% – Cyprus

18.10% – Chile

17.90% – Bosnia and Herzegovina

17.80% – Portugal

17.60% – Sweden

17.30% – Denmark

17.30% – France

17.20% – Namibia

16.80% – Iran

16.60% – Germany

15.60% – Malasya

15.30% – Israel

15.10% – Norway

14.90% – Belgium

14.30% – Netherlands

14% – Seychelles

10.90% – Switzerland

10% – Thailand

9.40% – Romania

9.20% – Austria

8.90% – Nigeria

7.80% – Sierra Leone

7.40% – Benin

6.90% – Indonesia

5.90% – Sri Lanka

5.50% – Afghanistan

3.90% – India

3.60% – Bangladesh

2.80% – Philippines

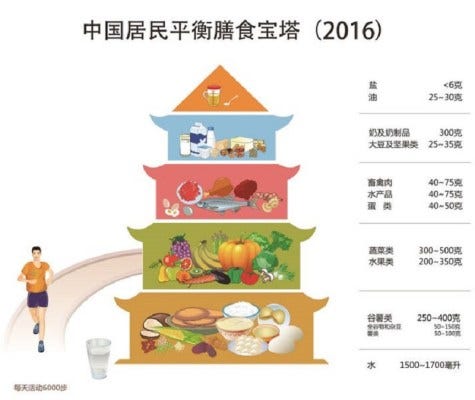

2.50% – China

2.50% – Japan

1.90% – Cambodia

1.70% – Vietnam

1.60% – Republic of Korea

As we can see, the dietary guidelines are essentially the same around the world, despite widely varying rates of obesity in each country that has adopted them.

But could, perhaps, the difference be in how long the guidelines have been in place? In the US they have been around since the 1970s. A long time to work their magic, compared to say China where only been in place less than a decade.

Well, if the guidelines caused obesity, one would expect that the longer a country has had dietary guidelines, the higher the rate of obesity. But this does not quite work, either. Looking at the obesity prevalence of 72 countries vs. time since implementation of the dietary guidelines, we find that such a relationship does not exist:

This suggests that the dietary guidelines–which are essentially the same around the world–do not have any impact on the rate of obesity.

So should we stop scapegoating the dietary guidelines and start asking deeper questions? I’ve already told you my answer to that question. Of course, American politics has devolved into the lowest version of a clown show possible in the history of this country, so I don’t expect nuanced discussion in the public any time soon. But for those looking to understand the truth, well, here, as far as I can tell, it is.

In my lifetime, I have seen the change from my 1970s childhood (when we ate what would be considered an objectively crappy diet by modern standards but had lower rates of obesity) to today, when there is much more interest and emphasis on health and diet yet people are fatter than ever.

My observations:

1. When I was a child, groceries were proportionately more expensive than they are today. We ate a lot of canned vegetables, because they were cheaper. We also ate a lot of stuff like tuna noodle casserole (made with Campbell's soup), American chop suey (once again, hamburger and noodles held together with condensed soup), baloney sandwiches, grilled cheese, hot dogs, etc.. We only had salads and fresh veggies in the summer, when we grew them in our garden and when they were relatively cheap at the market. My mom was a good cook and made homemade soups and chilis, she made a few Hungarian specialties from time to time, but as a working mom our diet was heavy on the casserole-and-crockpot meals.

2. Snacking was discouraged. It was believed that snacks caused tooth decay and spoiled your appetite for dinner. I remember in the late '80s when some study showed that "grazers" were thinner than those who ate three square meals, and people interpreted this as a license to snack (usually in addition to the three square meals). The snack industry was happy to help out with an explosion of new and delightful snack foods.

3. I recall sugar being the "bad" food when I was a child. We were sometimes allowed to have Kool-Aid, but our moms were stingy with the sugar so it usually tasted kind of bad. If you were allowed to have cookies after school, it was two very small cookies washed down with a glass of milk. More than that would "give you cavities" and more importantly, "spoil your appetite". Naughty children were labeled "hyperactive" and it was usually blamed on sugar and bad parenting. At some point in the '80s, there was the change in emphasis that it was actually dietary fat that caused obesity, with the corresponding explosion in fat-free (but very sugary) processed foods.

4. When my mom passed away and I was clearing out her house, I realized her dinner plates (1950's and 1960's vintage) were the size of modern luncheon plates. Her "juice glasses" held about 4 oz. Her large classes were 8 oz. Compare that to modern 12-16 oz. glasses. Her coffee cups held 4 oz, whereas some of my modern coffee mugs hold 16 oz.! Thus, our portion sizes were SIGNIFICANTLY smaller than those today.

5. Eating out was expensive, so we only did it on special occasions. Also, there were simply not the variety of restaurants that there are today. I lived in a large town (pop. 60K) in a major metropolitan area, but our dining out options were fairly limited: pizza/Italian, Chinese, diner, steakhouse, deli, or (if you were rich and fancy) the French restaurant. We didn't get a fast food restaurant in town until 1980. Nowadays, I live in a small town (pop. 6,500) but within a 10 mile range I can eat Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Lebanese, Mexican, Spanish, Greek...in addition to the basic American and Italian fare. The small, locally-owned shops and businesses of my youth are all gone, but a plethora of tasty ethnic restaurants have replaced them.

6. It was normal for kids to play outside, ride bikes, walk to school, etc.. And we wanted to be outside, because there was nothing interesting inside - afternoon TV was all soap operas or religious shows, there was no internet or video games, and if you were inside your parents would make you do chores. That is definitely not the case any more. My kids (early 2000s) had an analog childhood, but we were fighting the trend by not having cable or allowing them to use the computer.

7. Everyday living required more moving around. My parents had only one car until the mid-70's, so my mom and I walked to do errands during the day. Many of the older ladies in our neighborhood did not drive; and many families had only one car so it was normal to walk to the store, to the post office, to the pharmacy. As a teen, I thought nothing of walking 4 miles to the beach every day in the summer. And we would walk MILES to the party spot on the weekend, only to find the cops had kicked everyone out already and we'd have to walk around town looking for our friends to hang out with them. I walked so much that I regularly wore out the soles of my shoes.

8. Even office jobs required more walking around. When I started working at a corporate job in 1990, I had to walk around the building to pass out memos, make copies, use the fax machine, get office supplies - even just asking someone a question involved getting up off my butt and walking downstairs to Accounting or whatever. Nowadays, I work from home and I could literally remain in my chair all day if I felt like it.

9. A factor that I think is underrated is the invention of stretchy, comfortable, expandable fabrics. Jeans in the 1980s were heavy, rigid denim and if you gained a couple pounds, they were VERY uncomfortable and constricting. It usually served as a wakeup call that "hey, maybe I've been eating too much!" Clothing in general had no stretch and was much more structured, so you couldn't continue to cram yourself into your pants when you put on weight. In the mid-90's, I first started seeing jeans with some stretch in them, and by the early 2000's it was common to see people stuffing themselves into jeans that were a few sizes too small because the fabric was very accommodating. Also, in the '70s and 80's you just didn't wear athletic clothing unless you were exercising. It would have been kind of unthinkable to wear sweatpants or leggings to school, for example. It is rather ironic that with the rise in "athleisure" clothing, people became fatter and fatter.

Kevin, Well this was fascinating, Will have to use it appropriately on both sides of this aisle. The question is, if the guidance is not the cause...what is?